Navajo Language Utah Is Known for Jewelry Design and Peforming Arts

Manuelito, a chief of the Navajo. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 399,494 enrolled tribal members[1] (2021) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States (Navajo Nation, Arizona, Colorado, New United mexican states, Utah). Canada: 700 Residents of Canada identified as having Navajo Beginnings in the 2016 Canadian Census.[2] | |

| Languages | |

| Navajo, English, Spanish | |

| Organized religion | |

| Indigenous Faith, Native American Church, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Apachean (Southern Athabascan) peoples, Dene (Northern Athabascan) peoples |

The Navajo (; British English: Navaho; Navajo: Diné or Naabeehó ) are a Native American people of the Southwestern Usa.

At more than than 399,494 enrolled tribal members as of 2021[update],[1] [iii] the Navajo Nation is the largest federally recognized tribe in the U.Due south. (the Cherokee Nation being the second largest); the Navajo Nation has the largest reservation in the country. The reservation straddles the Iv Corners region and covers more than 27,000 square miles (70,000 square km) of land in Arizona, Utah and New Mexico. The Navajo language is spoken throughout the region, and nearly Navajos also speak English.

The states with the largest Navajo populations are Arizona (140,263) and New Mexico (108,306). More than three-quarters of the enrolled Navajo population resides in these two states.[4]

As well the Navajo Nation proper, a small group of ethnic Navajos are members of the federally recognized Colorado River Indian Tribes.

History [edit]

Early history [edit]

Navajos spinning and weaving

The Navajos are speakers of a Na-Dené Southern Athabaskan language which they call Diné bizaad (lit. 'People's language'). The term Navajo comes from Castilian missionaries and historians who referred to the Pueblo Indians through this term, although they referred to themselves as the Diné, is a compound word significant up where at that place is no surface, and then down to where nosotros are on the surface of Mother World. [v] The language comprises two geographic, mutually intelligible dialects. The Apache language is closely related to the Navajo Linguistic communication; the Navajos and Apaches are believed to have migrated from northwestern Canada and eastern Alaska, where the majority of Athabaskan speakers reside.[6] Speakers of various other Athabaskan languages located in Canada may still embrace the Navajo language despite the geographic and linguistic deviation of the languages.[7] Additionally, some Navajos speak Navajo Sign Language, which is either a dialect or girl of Plains Sign Talk. Some as well speak Plains Sign Talk itself.[8]

Archaeological and historical evidence suggests the Athabaskan ancestors of the Navajos and Apaches entered the Southwest around 1400 Advertizing.[9] [10] The Navajo oral tradition is transcribed to retain references to this migration.[ commendation needed ]

Initially, the Navajos were largely hunters and gatherers. Later, they adopted farming from Pueblo peoples, growing mainly the traditional "Three Sisters" of corn, beans, and squash. They adopted herding sheep and goats from the Spanish as a main source of merchandise and food. Meat became essential in the Navajo nutrition. Sheep became a class of currency and family status.[xi] [12] Women began to spin and weave wool into blankets and clothing; they created items of highly valued creative expression, which were also traded and sold.

Oral history indicates a long relationship with Pueblo people[13] and a willingness to contain Puebloan ideas and linguistic variance. At that place were long-established trading practices betwixt the groups. Mid-16th century Spanish records recount that the Pueblo exchanged maize and woven cotton goods for bison meat, hides, and rock from Athabaskans traveling to the pueblos or living nearby. In the 18th century, the Spanish reported that the Navajos' maintained large herds of livestock and cultivated large crop areas.[ citation needed ]

Western historians believe that the Spanish before 1600 referred to the Navajos as Apaches or Quechos.[fourteen] : ii–4 Fray Geronimo de Zarate-Salmeron, who was in Jemez in 1622, used Apachu de Nabajo in the 1620s to refer to the people in the Chama Valley region, east of the San Juan River and northwest of present-day Santa Iron, New United mexican states. Navahu comes from the Tewa language, meaning a large area of cultivated lands.[14] : 7–8 By the 1640s, the Castilian began using the term Navajo to refer to the Diné.

During the 1670s, the Spanish wrote that the Diné lived in a region known every bit Dinétah , about 60 miles (97 km) west of the Rio Chama valley region. In the 1770s, the Spanish sent military expeditions against the Navajos in the Mount Taylor and Chuska Mount regions of New United mexican states.[14] : 43–50 The Spanish, Navajos and Hopis continued to trade with each other and formed a loose alliance to fight Apache and Comanche bands for the next twenty years. During this time there were relatively minor raids by Navajo bands and Spanish citizens confronting each other.

In 1800 Governor Chacon led 500 men to the Tunicha Mountains confronting the Navajo. Twenty Navajo chiefs asked for peace. In 1804 and 1805 the Navajos and Castilian mounted major expeditions confronting each other's settlements. In May 1805 some other peace was established. Like patterns of peace-making, raiding, and trading among the Navajo, Spanish, Apache, Comanche, and Hopi continued until the inflow of Americans in 1846.[14]

Territory of New United mexican states 1846–1863 [edit]

The Navajos encountered the The states Army in 1846, when General Stephen W. Kearny invaded Santa Iron with 1,600 men during the Mexican–American War. On Nov 21, 1846, following an invitation from a small party of American soldiers under the command of Helm John Reid, who journeyed deep into Navajo land and contacted him, Narbona and other Navajos negotiated a treaty of peace with Colonel Alexander Doniphan at Bear Springs, Ojo del Oso (after the site of Fort Wingate). This understanding was not honored by some Navajo, nor past some New Mexicans. The Navajos raided New Mexican livestock, New Mexicans took women, children, and livestock from the Navajo.[15]

In 1849, the war machine governor of New Mexico, Colonel John MacRae Washington—accompanied by John Southward. Calhoun, an Indian agent—led 400 soldiers into Navajo state, penetrating Canyon de Chelly. He signed a treaty with two Navajo leaders: Mariano Martinez as Head Chief and Chapitone as Second Chief. The treaty acknowledged the transfer of jurisdiction from the United Mexican States to the Us. The treaty allowed forts and trading posts to be built on Navajo land. In exchange, the United states, promised "such donations [and] such other liberal and humane measures, as [it] may deem meet and proper."[16] While en route to sign this treaty, the prominent Navajo peace leader Narbona, was killed, causing hostility between the treaty parties.[17]

During the next ten years, the U.S. established forts on traditional Navajo territory. Military records cite this evolution every bit a precautionary measure to protect citizens and the Navajos from each other. Nonetheless, the Castilian/Mexican-Navajo pattern of raids and expeditions continued. Over 400 New Mexican militia conducted a campaign against the Navajo, against the wishes of the Territorial Governor, in 1860–61. They killed Navajo warriors, captured women and children for slaves, and destroyed crops and dwellings. The Navajos telephone call this period Naahondzood, "the fearing fourth dimension."

In 1861, Brigadier-Full general James H. Carleton, Commander of the Federal District of New Mexico, initiated a series of military actions against the Navajos and Apaches. Colonel Kit Carson was at the new Fort Wingate with Regular army troops and volunteer New Mexico militia. Carleton ordered Carson to kill Mescalero Apache men and destroy any Mescalero holding he could observe. Carleton believed these harsh tactics would bring whatsoever Indian Tribe nether control. The Mescalero surrendered and were sent to the new reservation chosen Bosque Redondo.

In 1863, Carleton ordered Carson to apply the same tactics on the Navajo. Carson and his strength swept through Navajo land, killing Navajos and destroying crops and dwellings, fouling wells, and capturing livestock. Facing starvation and death, Navajo groups came in to Fort Defiance for relief. On July twenty, 1863, the outset of many groups departed to join the Mescalero at Bosque Redondo. Other groups connected to come up in though 1864.[18]

However, not all the Navajos came in or were plant. Some lived near the San Juan River, some beyond the Hopi villages, and others lived with Apache bands.[19]

Long Walk [edit]

Beginning in the spring of 1864, the Ground forces forced effectually 9,000 Navajo men, women, and children to walk over 300 miles (480 km) to Fort Sumner, New Mexico, for internment at Bosque Redondo. The internment was disastrous for the Navajo, as the regime failed to provide enough h2o, wood, provisions, and livestock for the 4,000–5,000 people. Large-scale ingather failure and disease were also endemic during this time, as were raids by other tribes and civilians. Some Navajos froze in the winter considering they could make simply poor shelters from the few materials they were given. This period is known among the Navajos as "The Fearing Time".[xx] In addition, a small-scale group of Mescalero Apache, longtime enemies of the Navajos had been relocated to the area. Conflicts resulted.

In 1868, the Treaty of Bosque Redondo was negotiated between Navajo leaders and the federal regime assuasive the surviving Navajos to render to a reservation on a portion of their former homeland.

Reservation era [edit]

Navajo woman and child, circa 1880–1910

The United states of america military continued to maintain forts on the Navajo reservation in the years later on the Long Walk. From 1873 to 1895, the military employed Navajos equally "Indian Scouts" at Fort Wingate to help their regular units.[21] During this period, Master Manuelito founded the Navajo Tribal Police. Information technology operated from 1872 to 1875 as an anti-raid task force working to maintain the peaceful terms of the 1868 Navajo treaty.

By treaty, the Navajos were allowed to go out the reservation for trade, with permission from the military or local Indian agent. Eventually, the arrangement led to a gradual stop in Navajo raids, equally the tribe was able to increase their livestock and crops. Also, the tribe gained an increase in the size of the Navajo reservation from 3.v million acres (fourteen,000 km2; 5,500 sq mi) to the sixteen 1000000 acres (65,000 km2; 25,000 sq mi) as it stands today. Only economical conflicts with non-Navajos continued for many years as civilians and companies exploited resources assigned to the Navajo. The United states authorities made leases for livestock grazing, took land for railroad development, and permitted mining on Navajo land without consulting the tribe.

In 1883, Lt. Parker, accompanied by 10 enlisted men and two scouts, went up the San Juan River to separate the Navajos and citizens who had encroached on Navajo land.[22] In the same year, Lt. Lockett, with the aid of 42 enlisted soldiers, was joined by Lt. Holomon at Navajo Springs. Evidently, citizens of the surnames Houck and/or Owens had murdered a Navajo principal's son, and 100 armed Navajo warriors were looking for them.

In 1887, citizens Palmer, Lockhart, and King made a charge of equus caballus stealing and randomly attacked a domicile on the reservation. Two Navajo men and all three whites died as a event, but a adult female and a child survived. Capt. Kerr (with 2 Navajo scouts) examined the ground and so met with several hundred Navajos at Houcks Tank. Rancher Bennett, whose horse was allegedly stolen, told Kerr that his horses were stolen by the three whites to take hold of a horse thief.[23] In the same year, Lt. Scott went to the San Juan River with ii scouts and 21 enlisted men. The Navajos believed Scott was at that place to drive off the whites who had settled on the reservation and had fenced off the river from the Navajo. Scott found evidence of many not-Navajo ranches. Only three were active, and the owners wanted payment for their improvements before leaving. Scott ejected them.[24]

In 1890, a local rancher refused to pay the Navajos a fine of livestock. The Navajos tried to collect information technology, and whites in southern Colorado and Utah claimed that 9,000 of the Navajos were on a warpath. A small armed forces detachment out of Fort Wingate restored white citizens to club.[ citation needed ]

In 1913, an Indian agent ordered a Navajo and his iii wives to come up in, and then arrested them for having a plural union. A small grouping of Navajos used force to gratis the women and retreated to Beautiful Mountain with xxx or 40 sympathizers. They refused to surrender to the agent, and local police enforcement and armed forces refused the amanuensis's request for an armed date. General Scott arrived, and with the assistance of Henry Chee Dodge, a leader among the Navajo, defused the situation.[ commendation needed ]

Boarding schools and education [edit]

During the time on the reservation, the Navajo tribe was forced to assimilate to white order. Navajo children were sent to boarding schools within the reservation and off the reservation. The first Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) school opened at Fort Defiance in 1870[25] and led the way for viii others to be established.[26] Many older Navajos were against this education and would hide their children to keep them from being taken.

Once the children arrived at the boarding school, their lives changed dramatically. European Americans taught the classes under an English language-only curriculum and punished whatever educatee caught speaking Navajo.[26] The children were nether militaristic subject, run by the Siláo.[ description needed ] In multiple interviews, subjects recalled being captured and disciplined by the Siláo if they tried to run abroad. Other atmospheric condition included inadequate food, overcrowding, required transmission labor in kitchens, fields, and boiler rooms; and military-style uniforms and haircuts.[27]

Alter did not occur in these boarding schools until later on the Meriam Report was published in 1929 past the Secretary of Interior, Hubert Work. This report discussed Indian boarding schools equally beingness inadequate in terms of diet, medical services, dormitory overcrowding, undereducated teachers, restrictive bailiwick, and transmission labor by the students to continue the schoolhouse running.[28]

This report was the forerunner to education reforms initiated nether President Franklin D. Roosevelt, under which two new schools were congenital on the Navajo reservation. But Crude Rock Mean solar day School was run in the aforementioned militaristic style as Fort Defiance and did not implement the educational reforms. The Evangelical Missionary Schoolhouse was opened next to Rough Rock Twenty-four hour period School. Navajo accounts of this schoolhouse portray it as having a family-like atmosphere with home-cooked meals, new or gently used article of clothing, humane handling, and a Navajo-based curriculum. Educators establish the Evangelical Missionary School curriculum to be much more beneficial for the Navajo children.[29]

In 1937, Boston heiress Mary Cabot Wheelright and Navajo singer and medicine human Hastiin Klah founded the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian in Santa Iron. It is a repository for sound recordings, manuscripts, paintings, and sandpainting tapestries of the Navajos. Information technology besides featured exhibits to express the dazzler, dignity, and logic of Navajo organized religion. When Klah met Cabot in 1921, he had witnessed decades of efforts by the US government and missionaries to assimilate the Navajos into mainstream society. The museum was founded to preserve the religion and traditions of the Navajo, which Klah was certain would otherwise before long be lost forever.

The result of these boarding schools led to much linguistic communication loss within the Navajo Nation. Later the 2nd World War, the Meriam Report funded more children to attend these schools with six times as many children attention boarding school than before the War.[xxx] English equally the chief language spoken at these schools every bit well equally the local towns surrounding the Navajo reservations contributed to residents condign bilingual; even so Navajo was the even so the primary linguistic communication spoken at dwelling house.[30]

Livestock Reduction 1930s–1950s [edit]

The Navajo Livestock Reduction was imposed upon the Navajo Nation past the federal government starting in the 1933, during the Bully Depression.[31] Under various forms information technology continued into the 1950s. Worried about big herds in the arid climate, at a time when the Dust Bowl was endangering the Bang-up Plains, the government decided that the land of the Navajo Nation could back up just a fixed number of sheep, goats, cattle, and horses. The Federal government believed that state erosion was worsening in the area and the but solution was to reduce the number of livestock.

In 1933, John Collier was appointed commissioner of the BIA. In many ways, he worked to reform government relations with the Native American tribes, but the reduction program was devastating for the Navajo, for whom their livestock was so important. The government set land capacity in terms of "sheep units". In 1930 the Navajos grazed ane,100,000 mature sheep units.[32] These sheep provided half the greenbacks income for the individual Navajo.[33]

Collier's solution was to first launch a voluntary reduction program, which was fabricated mandatory two years later in 1935. The government paid for part of the value of each animate being, only it did nothing to compensate for the loss of future yearly income for so many Navajo. In the matrilineal and matrilocal world of the Navajo, women were specially hurt, as many lost their only source of income with the reduction of livestock herds.[34]

The Navajos did not empathize why their centuries-old practices of raising livestock should alter.[32] They were united in opposition simply they were unable to stop it.[35] Historian Brian Dippie notes that the Indian Rights Association denounced Collier as a 'dictator' and accused him of a "nearly reign of terror" on the Navajo reservation. Dippie adds that, "He became an object of 'burning hatred' among the very people whose problems so preoccupied him."[36] The long-term result was strong Navajo opposition to Collier'south Indian New Deal.[37]

[edit]

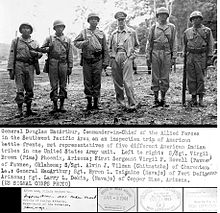

General Douglas MacArthur coming together Navajo, Pima, Pawnee and other Native American troops

Many Navajo young people moved to cities to work in urban factories in Globe War 2. Many Navajo men volunteered for armed forces service in keeping with their warrior culture, and they served in integrated units. The War Department in 1940 rejected a proposal past the BIA that segregated units be created for the Indians. The Navajos gained firsthand experience with how they could assimilate into the mod world, and many did not render to the overcrowded reservation, which had few jobs.[38]

Four hundred Navajo lawmaking talkers played a famous role during World War Two by relaying radio messages using their ain language. The Japanese were unable to sympathize or decode it.[39]

In the 1940s, large quantities of uranium were discovered in Navajo country. From then into the early 21st century, the U.South. allowed mining without sufficient ecology protection for workers, waterways, and country. The Navajos take claimed high rates of decease and disease from lung disease and cancer resulting from environmental contamination. Since the 1970s, legislation has helped to regulate the industry and reduce the cost, simply the regime has not yet offered holistic and comprehensive bounty.[forty]

U.S. Marine Corps Involvement [edit]

The Navajo Code Talkers played a significant role in USMC history. Using their own language they utilized a military code; for example, the Navajo word "turtle" represented a tank. In 1942, Marine staff officers equanimous several combat simulations and the Navajo translated it and transmitted it in their dialect to another Navajo on the other line. This Navajo then translated it back in English faster than whatever other cryptographic facilities, which demonstrated their efficacy. Every bit a result, General Vogel recommended their recruitment into the USMC lawmaking talker program.

Each Navajo went through basic bootcamp at Marine Corps Recruit Depot, San Diego earlier existence assigned to Field Bespeak Battalion training at Camp Pendleton. Once the lawmaking talkers completed training in the States, they were sent to the Pacific for consignment to the Marine gainsay divisions. With that said, there was never a crack in the Navajo linguistic communication, it was never deciphered. Information technology is known that many more than Navajos volunteered to go code talkers than could exist accepted; yet, an undetermined number of other Navajos served as Marines in the war, just not as code talkers.

These achievements of the Navajo Code Talkers have resulted in an honorable chapter in USMC history. Their patriotism and honour inevitably earned them the respect of all Americans.[41]

After 1945 [edit]

| | This department needs expansion. Yous can assist by adding to information technology. (August 2016) |

Culture [edit]

Dibé (sheep) remain an important aspect of Navajo culture.

The name "Navajo" comes from the late 18th century via the Spanish (Apaches de) Navajó "(Apaches of) Navajó", which was derived from the Tewa navahū "subcontract fields adjoining a valley". The Navajos call themselves Diné .[42]

Like other Apacheans, the Navajos were semi-nomadic from the 16th through the 20th centuries. Their extended kinship groups had seasonal dwelling areas to accommodate livestock, agronomics, and gathering practices. As part of their traditional economic system, Navajo groups may have formed trading or raiding parties, traveling relatively long distances.

In that location is a system of clans which defines relationships between individuals and families. The clan system is exogamous: people can only marry (and date) partners outside their own clans, which for this purpose include the clans of their iv grandparents. Some Navajos favor their children to marry into their father'south clan. While clans are associated with a geographical area, the area is not for the exclusive apply of any one clan. Members of a clan may live hundreds of miles autonomously but notwithstanding have a clan bond.[nineteen] : nineteen–xxi

Historically, the structure of the Navajo gild is largely a matrilineal system, in which the family of the women owned livestock, dwellings, planting areas and livestock grazing areas. Once married, a Navajo human being would follow a matrilocal residence and alive with his helpmate in her dwelling house and near her female parent's family unit. Daughters (or, if necessary, other female relatives) were traditionally the ones who received the generational property inheritance. In cases of marital separation, women would maintain the property and children. Children are "born to" and belong to the mother'southward association, and are "born for" the begetter'due south clan. The mother'southward eldest brother has a strong role in her children'due south lives. Equally adults, men stand for their mother'due south clan in tribal politics.[42]

Neither sex activity can alive without the other in the Navajo culture. Men and women are seen every bit contemporary equals as both a male person and female are needed to reproduce. Although women may bear a bigger burden, fertility is so highly valued that males are expected to provide economic resources (known equally bride wealth). Corn is a symbol of fertility in Navajo civilization as they eat white corn in the hymeneals ceremonies. It is considered to exist immoral and/or stealing if one does not provide for the other in that premarital or marital relationship.[43]

Ethnobotany [edit]

Run into Navajo ethnobotany.

Traditional dwellings [edit]

Hogan at Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park

A hogan, the traditional Navajo dwelling, is built every bit a shelter for either a man or for a woman. Male hogans are square or conical with a singled-out rectangular entrance, while a female person hogan is an eight-sided business firm.[ citation needed ] Hogans are made of logs and covered in mud, with the door always facing east to welcome the sun each morning time. Navajos too have several types of hogans for lodging and ceremonial apply. Ceremonies, such as healing ceremonies or the kinaaldá, take identify inside a hogan.[44] According to Kehoe, this manner of housing is distinctive to the Navajos. She writes, "fifty-fifty today, a solidly constructed, log-walled Hogan is preferred past many Navajo families." Most Navajo members today live in apartments and houses in urban areas.[45]

Those who do the Navajo religion regard the hogan as sacred. The religious song "The Blessingway" ( hózhǫ́ǫ́jí ) describes the kickoff hogan equally being built past Coyote with help from Beavers to be a house for First Man, Start Woman, and Talking God. The Beaver People gave Coyote logs and instructions on how to build the first hogan. Navajos made their hogans in the traditional fashion until the 1900s, when they started to make them in hexagonal and octagonal shapes. Hogans continue to be used equally dwellings, peculiarly past older Navajos, although they tend to be made with mod structure materials and techniques. Some are maintained specifically for ceremonial purposes.[ citation needed ]

Spiritual and religious beliefs [edit]

Navajo Yebichai (Yei Bi Chei) dancers. Edward S. Curtis. USA, 1900. The Wellcome Drove, London

Navajo spiritual practice is about restoring balance and harmony to a person's life to produce health and is based on the ideas of Hózhóójí. The Diné believed in 2 classes of people: Earth People and Holy People. The Navajo people believe they passed through three worlds before arriving in this world, the 4th World or the Glittering World. As Earth People, the Diné must do everything within their power to maintain the remainder between Mother Earth and man.[46] The Diné likewise had the expectation of keeping a positive relationship between them and the Diyin Diné. In the Diné Bahane' (Navajo beliefs about creation), the Offset, or Dark World is where the four Diyin Diné lived and where First Adult female and First Human being came into existence. Because the globe was so dark, life could not thrive there and they had to move on. The 2nd, or Blue World, was inhabited by a few of the mammals Earth People know today equally well as the Swallow Master, or Táshchózhii. The First World beings had offended him and were asked to leave. From at that place, they headed south and arrived in the Third Globe, or Yellow Globe. The four sacred mountains were found here, simply due to a not bad inundation, Outset Woman, Kickoff Man, and the Holy People were forced to detect another earth to live in. This time, when they arrived, they stayed in the Fourth World. In the Glittering World, true death came into existence, too as the creations of the seasons, the moon, stars, and the sun.[47]

The Holy People, or Diyin Diné, had instructed the Globe People to view the iv sacred mountains every bit the boundaries of the homeland ( Dinétah ) they should never leave: Blanca Summit ( Sisnaajiní — Dawn or White Shell Mount) in Colorado; Mount Taylor ( Tsoodził — Bluish Dewdrop or Turquoise Mountain) in New Mexico; the San Francisco Peaks ( Dookʼoʼoosłííd — Abalone Beat out Mountain) in Arizona; and Hesperus Mountain ( Dibé Nitsaa — Big Mount Sheep) in Colorado.[48] Times of day, besides every bit colors, are used to represent the 4 sacred mountains. Throughout religions, the importance of a specific number is emphasized and in the Navajo religion, the number four appears to be sacred to their practices. For example, there were four original clans of Diné, iv colors and times of 24-hour interval, four Diyin Diné, and for the near office, four songs sung for a ritual.[48]

Navajos have many different ceremonies. For the most part, their ceremonies are to prevent or cure diseases.[49] Corn pollen is used every bit a approving and as an offering during prayer.[46] One half of major Navajo song ceremonial complex is the Blessing Way (Hózhǫ́ǫ́jí) and other half is the Enemy Style (Anaʼí Ndááʼ). The Approval Way ceremonies are based on establishing "peace, harmony, and good things exclusively" within the Dine. The Enemy Way, or Evil Way ceremonies are concerned with counteracting influences that come from exterior the Dine.[49] Spiritual healing ceremonies are rooted in Navajo traditional stories. One of them, the Night Chant ceremony, is conducted over several days and involves up to 24 dancers. The ceremony requires the dancers to clothing buckskin masks, as do many of the other Navajo ceremonies, and they all correspond specific gods.[49] The purpose of the Nighttime Chant is to purify the patients and heal them through prayers to the spirit-beings. Each day of the ceremony entails the performance of certain rites and the creation of detailed sand paintings. One of the songs describes the abode of the thunderbirds:

In Tsegihi [White Business firm],

In the house made of the dawn,

In the firm made of the evening light[fifty]

The ceremonial leader gain by asking the Holy People to be present at the beginning of the anniversary, then identifying the patient with the power of the spirit-being, and describing the patient's transformation to renewed wellness with lines such equally, "Happily I recover."[51]

Ceremonies are used to correct curses that cause some illnesses or misfortunes. People may complain of witches who do damage to the minds, bodies, and families of innocent people,[52] though these matters are rarely discussed in detail with those outside of the community.[53]

Oral Stories / Works of Literature [edit]

See: Diné Bahane' (Cosmos Story) and Black God and Coyote (notable traditional characters)

The Navajo Tribe relied on oral tradition to maintain behavior and stories. Examples would include the traditional creation story Diné Bahane'.[46] In that location are besides some Navajo Indian legends that are staples in literature, including The First Man and First Woman [54] likewise as The Sun, Moon and Stars.[55] The Start Man and Woman is a myth nigh the creation of the world, and The Dominicus, Moon and Stars is a legend about the origin of heavenly bodies.

Music [edit]

Visual arts [edit]

Silverwork [edit]

Silversmithing is an important art form amongst Navajos. Atsidi Sani (c. 1830–c. 1918) is considered to be the first Navajo silversmith. He learned silversmithing from a Mexican man called Nakai Tsosi ("Sparse Mexican") around 1878 and began pedagogy other Navajos how to work with silver.[56] Past 1880, Navajo silversmiths were creating handmade jewelry including bracelets, tobacco flasks, necklaces and bracers. Later, they added silver earrings, buckles, bolos, pilus ornaments, pins and squash blossom necklaces for tribal use, and to sell to tourists equally a manner to supplement their income.[57]

The Navajos' hallmark jewelry piece chosen the "squash blossom" necklace first appeared in the 1880s. The term "squash blossom" was obviously fastened to the proper noun of the Navajo necklace at an early date, although its bud-shaped chaplet are thought to derive from Spanish-Mexican pomegranate designs.[58] The Navajo silversmiths also borrowed the "naja" (najahe in Navajo)[59] symbol to shape the silverish pendant that hangs from the "squash bloom" necklace.

Turquoise has been part of jewelry for centuries, but Navajo artists did not utilize inlay techniques to insert turquoise into silvery designs until the late 19th century.

Weaving [edit]

Probably Bayeta-style Blanket with Terrace and Stepped Design, 1870–1880, 50.67.54, Brooklyn Museum

Navajos came to the southwest with their own weaving traditions; nevertheless, they learned to weave cotton fiber on upright looms from Pueblo peoples. The first Spaniards to visit the region wrote nigh seeing Navajo blankets. By the 18th century, the Navajos had begun to import Bayeta reddish yarn to supplement local black, grey, and white wool, also as wool dyed with indigo. Using an upright loom, the Navajos made extremely fine commonsensical blankets that were collected by Ute and Plains Indians. These Chief's Blankets, so called because but chiefs or very wealthy individuals could afford them, were characterized by horizontal stripes and minimal patterning in blood-red. Start Phase Chief's Blankets accept only horizontal stripes, Second Phase feature ruby rectangular designs, and 3rd Phase features red diamonds and partial diamond patterns.

The completion of the railroads dramatically inverse Navajo weaving. Inexpensive blankets were imported, and then Navajo weavers shifted their focus to weaving rugs for an increasingly non-Native audience. Rail service also brought in Germantown wool from Philadelphia, commercially dyed wool which greatly expanded the weavers' colour palettes.

Some early European-American settlers moved in and ready trading posts, often buying Navajo rugs past the pound and selling them back east by the bale. The traders encouraged the locals to weave blankets and rugs into distinct styles. These included "Two Greyness Hills" (predominantly black and white, with traditional patterns); Teec Nos Pos (colorful, with very extensive patterns); "Ganado" (founded by Don Lorenzo Hubbell[60]), red-dominated patterns with black and white; "Crystal" (founded past J. B. Moore); oriental and Persian styles (virtually always with natural dyes); "Wide Ruins", "Chinlee", banded geometric patterns; "Klagetoh", diamond-type patterns; "Blood-red Mesa" and assuming diamond patterns.[61] Many of these patterns exhibit a fourfold symmetry, which is thought to embody traditional ideas virtually harmony or hózhǫ́.

In the media [edit]

In 2000 the documentary The Return of Navajo Boy was shown at the Sundance Motion picture Festival. Information technology was written in response to an earlier motion picture, The Navajo Male child which was somewhat exploitative of those Navajos involved. The Return of Navajo Boy immune the Navajos to be more involved in the depictions of themselves.[62]

In the last episode of the third season of the FX reality TV evidence 30 Days, the show's producer Morgan Spurlock spends thirty days living with a Navajo family on their reservation in New Mexico. The July 2008 show called "Life on an Indian Reservation", depicts the dire conditions that many Native Americans experience living on reservations in the United States.[ citation needed ]

Tony Hillerman wrote a series of detective novels whose detective characters were members of the Navajo Tribal Police. The novels are noted for incorporating details about Navajo culture, and in some cases expand the focus to include nearby Hopi and Zuni characters and cultures, as well.[ citation needed ] Four of the novels have been adapted for motion picture/Television set. His daughter has continued the novel series after his death.

In 1997, Welsh author Eirug Wyn published the Welsh-language novel "I Ble'r Aeth Haul y Bore?" ("Where did the Morning Sun go?" in English) which tells the story of Carson'due south misdoings against the Navajo people from the point of view of a fictional young Navajo adult female chosen "Haul y Diameter" ("Forenoon Sun" in English).[63]

[edit]

- Fred Begay, nuclear physicist and a Korean War veteran

- Notah Begay Iii (Navajo-Isleta-San Felipe Pueblo), American professional golfer

- Klee Benally, musician and documentary filmmaker[64]

- Nikki Cooley, environmentalist, Grand Canyon river guide[65]

- Jacoby Ellsbury, New York Yankees outfielder (enrolled Colorado River Indian Tribes)

- Rickie Fowler, American professional golfer

- Joe Kieyoomia, captured by the Imperial Japanese Ground forces after the fall of the Philippines in 1942

- Nicco Montaño, sometime women'due south UFC flyweight champion

- Chester Nez, the last original Navajo code talker who served in the U.s.a. Marine Corps during World War II.

- Krystal Tsosie, geneticist and bioethicist known for promoting Indigenous information sovereignty and studying genetics within Indigenous communities

- Lance Tsosie, TikToker whose videos hash out North American Native civilization and history.

- Cory Witherill, commencement pedigree Native American in NASCAR

- Aaron Yazzie, mechanical engineer at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Artists [edit]

- Beatien Yazz (born 1928), painter

- Apie Begay (fl. 1902), first Navajo artist to utilise European drawing materials

- Harrison Begay (1914–2012), Studio painter

- Joyce Begay-Foss, weaver, educator, and museum curator

- Mary Holiday Black (built-in c. 1934), basket maker

- Raven Chacon (born 1977), conceptual artist

- Lorenzo Clayton (built-in 1940), artist

- Carl Nelson Gorman (also known as Kin-Ya-Onny-Beyeh; 1907–1998), painter, printmaker, illustrator, and Navajo code talker with the U.South. Marine Corp during World State of war II.

- R. C. Gorman (1932–2005), painter and printmaker

- Hastiin Klah, weaver and co-founder of the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian

- David Johns (born 1948), painter

- Yazzie Johnson, contemporary silversmith

- Betty Manygoats, Tàchii'nii, contemporary ceramicist

- Christine Nofchissey McHorse (1948-2021), ceramicist

- Gerald Nailor, Sr. (1917–1952), studio painter

- Barbara Teller Ornelas (born 1954), master Navajo weaver, cultural ambassador of the U.S. State Department

- Atsidi Sani (c. 1828–1918), first known Navajo silversmith

- Clara Nezbah Sherman, weaver

- Ryan Singer, painter, illustrator, screen printer

- Tommy Singer, silversmith and jeweler

- Quincy Tahoma (1920–1956), studio painter

- Klah Tso (mid-19th century — early 20th century), pioneering easel painter

- Emmi Whitehorse, gimmicky painter

- Melanie Yazzie, gimmicky print maker and educator

Performers [edit]

- Jeremiah Bitsui, actor

- Blackfire, punk/alternative rock ring

- Raven Chacon, composer

- Radmilla Cody, traditional vocalist

- James and Ernie, one-act duo

- R. Carlos Nakai, musician

- Jock Soto, ballet dancer

Politicians [edit]

- Christina Haswood, member of the Kansas House of Representatives since 2021

- Henry Chee Dodge, final Head Main of the Navajo and start Chairman of the Navajo Tribe, (1922–1928, 1942–1946).

- Peterson Zah, first President of the Navajo Nation and last Chairman of the Navajo Tribe.[66]

- Albert Hale, former President of the Navajo Nation. He served in the Arizona Senate from 2004 to 2011 and in the Arizona Firm of Representatives from 2011 to 2017.

- Jonathan Nez, Current President of the Navajo Nation. He served iii terms equally Navajo Council Delegate representing the chapters of Shonto, Oljato, Tsah Bi Kin and Navajo Mountain. Served two terms as Navajo County Board of Supervisors for District ane.

- Annie Dodge Wauneka, sometime Navajo Tribal Councilwoman and abet.

- Thomas Dodge, former Chairman of the Navajo Tribe and offset Diné chaser.

- Peter MacDonald, Navajo Code Talker and former Chairman of the Navajo Tribe.

- Marking Maryboy (Aneth/Cerise Mesa/Mexican Water), sometime Navajo Nation Council Delegate, working in Utah Navajo Investments.

- Lilakai Julian Neil, the showtime adult female elected to Navajo Tribal Quango.

- Joe Shirley, Jr., sometime President of the Navajo Nation

- Ben Shelly, former President of the Navajo Nation.

- Chris Deschene, veteran, attorney, engineer, and a community leader. 1 of few Native Americans to be accepted into the U.Southward. Naval Academy in Annapolis. Upon graduation, he was commissioned as a 2nd Lt. in the U.South. Marine Corps. He made an unsuccessful try to run for Navajo Nation President.

Writers [edit]

- Freddie Bitsoie, author and chef

- Sherwin Bitsui, author and poet

- Luci Tapahonso, poet and lecturer

- Elizabeth Woody, author, educator, and environmentalist

See likewise [edit]

- Navajo-Churro sheep

- Navajo pueblitos

- Navajo Nation

- Long Walk of the Navajo

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b Becenti, Arlyssa. [1] Navajo Times 26 Apr 2021 (retrieved 26 April 2021)

- ^ "Aboriginal Population Profile, 2016 Census". www12.statcan.gc.ca/. Statistics Canada. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

- ^ "Arizona'due south Native American Tribes: Navajo Nation." Archived 2012-01-01 at the Wayback Machine University of Arizona, Tucson Economical Development Research Program. Retrieved 19 Jan 2011.

- ^ American Factfinder, United states Census Bureau

- ^ Haile, Berard (1949). "Navaho or Navajo?". The Americas. vi (1): 85–90. doi:10.2307/977783. ISSN 0003-1615. JSTOR 977783.

- ^ Watkins, Thayer. "Discovery of the Athabascan Origin of the Apache and Navajo Language." San Jose State Academy. (retrieved 28 Nov 2010)

- ^ Commencement Peoples' Cultural Foundation "Nearly Our Language." Offset Voices: Dene Welcome Folio. 2010 (retrieved 28 Nov 2010)

- ^ Samuel J. Supalla (1992) The Book of Name Signs, p. 22

- ^ Pritzker, 52

- ^ For example, the Great Canadian Parks website suggests the Navajos may be descendants of the lost Naha tribe, a Slavey tribe from the Nahanni region west of Great Slave Lake. "Nahanni National Park Reserve". Swell Canadian Parks. Retrieved 2007-07-02 .

- ^ Iverson, Nez, and Deer, 19

- ^ Iverson, Nez, and Deer, 62

- ^ Hosteen Klah, page 102 and others

- ^ a b c d Correll, J. Lee (1976). Through White Men's Eyes: A contribution to Navajo History (Book). Window Stone, AZ: The Navajo Times Publishing Visitor.

- ^ Pages 133 to 140 and 152 to 154, Sides, Claret and Thunder

- ^ nine Stat. 974

- ^ Simpson, James H, edited and annotated by Frank McNitt, foreword by Durwood Ball, Navaho Trek: Journal of a Military Reconnaissance from Santa Fe, New Mexico, to the Navajo Land, Fabricated in 1849, University of Oklahoma Press (1964), merchandise paperback (2003), 296 pages, ISBN 0-8061-3570-0

- ^ Thompson, Gerald (1976). The Army and the Navajo: The Bosque Redondo Reservation Experiment 1863–1868. Tucson, Arizona: The Academy of Arizona Press. ISBN9780816504954.

- ^ a b Compiled (1973). Roessel, Ruth (ed.). Navajo Stories of the Long Walk Menses . Tsaile, Arizona: Navajo Community Higher Printing. ISBN0-912586-xvi-8.

- ^ George Bornstein, "The Fearing Time: Telling the tales of Indian slavery in American history", Times Literary Supplement, 20 Oct 2017 p. 29 (review of Andrés Reséndez, The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, ISBN 9780547640983).

- ^ Marei Bouknight and others, Guide to Records in the Armed services Archives Division Pertaining to Indian-White Relations, GSA National Archives, 1972

- ^ Ford, "September thirty, 1887 Letter to Acting Assistant Full general," Commune of New Mexico, National Archive Materials, Navajo Tribal Museum, Window Rock, Arizona

- ^ Kerr, "February 18, 1887 letter to Acting Banana General," District of New Mexico, National Archive Materials, Navajo Tribal Museum, Window Rock, Arizona.

- ^ Scott," June 22, 1887 letter to Interim Assistant General," Commune of New Mexico, National Archive Materials, Navajo Tribal Museum, Window Rock, Arizona

- ^ "Fort Disobedience Chapter". FORT Defiance CHAPTER . Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ^ a b McCarty, T.L.; Bia, Fred (2002). A Place to be Navajo: Rough Rock and the Struggle for Self-Conclusion in Indigenous Schooling . Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. p. 42. ISBN0-8058-3760-4.

- ^ McCarty, T.L.; Bia, Fred (2002). A Identify to be Navajo: Rough Rock and the Struggle for Self-Determination in Ethnic Schooling . Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 44–5. ISBN0-8058-3760-4.

- ^ McCarty, T.L.; Bia, Fred (2002). A Identify to exist Navajo: Rough Rock and the Struggle for Self-Decision in Ethnic Schooling . Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. p. 48. ISBN0-8058-3760-4.

- ^ McCarty, T.L.; Bia, Fred (2002). A Place to be Navajo: Rough Rock and the Struggle for Self-Determination in Indigenous Schooling . Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 50–1. ISBN0-8058-3760-four.

- ^ a b Spolsky, Bernard (July 2014). "Linguistic communication Documentation and Clarification" (PDF) . Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ Peter Iverson, Dine: A History of the Navajos, 2002, University of New Mexico Printing, Affiliate v, "our People Cried": 1923–1941.

- ^ a b Compiled (1974). Roessel, Ruth (ed.). Navajo Livestock Reduction: A National Disgrace. Tsaile, Arizona: Navajo Community Higher Press. ISBN0-912586-eighteen-4.

- ^ Peter Iverson (2002). "For Our Navajo People": Diné Messages, Speeches & Petitions, 1900-1960. U of New Mexico Press. p. 250. ISBN9780826327185.

- ^ Weisiger, Marsha (2007). "Gendered Injustice: Navajo Livestock Reduction in the New Deal Era". Western Historical Quarterly. 38 (4): 437–455. doi:10.2307/25443605. JSTOR 25443605. S2CID 147597303.

- ^ Richard White, ch thirteen: "The Navajos become Dependent" (1988). The Roots of Dependency: Subsistence, Environment, and Social Change Among the Choctaws, Pawnees, and Navajos. U of Nebraska Press. pp. 300ff. ISBN0803297246.

- ^ Brian Due west. Dippie, The Vanishing American: White Attitudes and U.S. Indian Policy (1991) pp 333–336, quote p 335

- ^ Donald A. Grinde Jr, "Navajo Opposition to the Indian New Deal." Integrated Pedagogy (1981) 19#3–6 pp: 79–87.

- ^ Alison R. Bernstein, American Indians and World State of war II: Toward a New Era in Indian Affairs, (University of Oklahoma Press, 1999) pp 40, 67, 132, 152

- ^ Bernstein, American Indians and World War Two pp 46–49

- ^ Judy Pasternak, Yellow Dirt- An American Story of a Poisoned Land and a People Betrayed, Complimentary Press, New York, 2010.

- ^ Marine Corps. University, NAVAJO CODE TALKERS IN WORLD WAR II, USMC History Partition, 2006.

- ^ Lauren Del Carlo, Between the Sacred Mountains: A Cultural History of the Dineh, Essai, Volume v: Article xv, 2007.

- ^ Iverson, Nez, and Deer, 23

- ^ Kehoe, 133

- ^ a b c "Navajo Cultural History and Legends". www.navajovalues.com . Retrieved 2016-05-31 .

- ^ "The Story of the Emergence". www.sacred-texts.com . Retrieved 2016-05-31 .

- ^ a b "Navajo Culture". www.discovernavajo.com . Retrieved 2016-05-31 .

- ^ a b c Wyman, Leland (1983). "Navajo Ceremonial Arrangement" (PDF). Smithsonian Establishment. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- ^ Sandner, 88

- ^ Sandner, 90

- ^ Kluckhohn, Clyde (1967). Navaho Witchcraft . Boston: Beacon Printing. 080704697-3.

- ^ Keene, Dr. Adrienne, "Magic in Due north America Part i: Ugh." at Native Appropriations", eight March 2016. Accessed nine April 2016: "What happens when Rowling pulls this in, is we as Native people are at present opened up to a barrage of questions about these beliefs and traditions ... but these are non things that need or should exist discussed past outsiders. At all. I'm sorry if that seems "unfair," but that'south how our cultures survive."

- ^ "Cosmos of Start Man and First Woman - A Navajo Legend". www.firstpeople.usa . Retrieved 2021-ten-13 .

- ^ "The Sunday, Moon and Stars". www.hanksville.org . Retrieved 2021-10-xiii .

- ^ Adair four

- ^ Adair 135

- ^ Adair 44

- ^ Adair, 9

- ^ "Hubbell Trading Postal service National Celebrated Site" White Mountains Online. (retrieved 28 Nov 2010)

- ^ Denver Art Museum. "Coating Statements", Traditional Fine Arts Organization. (retrieved 28 Nov 2010)

- ^ "I Ble'r Aeth Haul y Bore? (9780862434359) | Eirug Wyn | Y Lolfa". www.ylolfa.com . Retrieved 2019-08-01 .

- ^ "Klee Benally". Nativenetworks.si.edu . Retrieved 2012-01-31 .

- ^ "Nikki Cooley to speak at climate summit June 9". Navajo-Hopi Observer. June 1, 2021. Retrieved March 29, 2022.

- ^ Peterson Zah Biography

References [edit]

- Adair, John. The Navajo and Pueblo Silversmiths. Norman: Oklahoma Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0-8061-2215-1.

- Iverson, Peter, Jennifer Nez Denetdale, and Ada E. Deer. The Navajo. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 2006. ISBN 0-7910-8595-3.

- Kehoe, Alice Brook. N American Indians: A Comprehensive business relationship. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 2005.

- Newcomb, Franc Johnson (1964). Hosteen Klah: Navajo Medicine Man and Sand Painter. Norman, Oklahoma: Academy of Oklahoma Press. LCCN 64020759.

- Pritzker, Barry M. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford: Oxford Academy Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1.

- Sandner, Donald. Navaho symbols of healing: a Jungian exploration of ritual, image, and medicine. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Printing, 1991. ISBN 978-0-89281-434-iii.

- Sides, Hampton, Claret and Thunder: An Ballsy of the American West. Doubleday (2006). ISBN 978-0-385-50777-6

Further reading [edit]

- Bailey, L. R. (1964). The Long Walk: A History of the Navaho Wars, 1846–1868.

- Bighorse, Tiana (1990). Bighorse the Warrior. Ed. Noel Bennett, Tucson: Academy of Arizona Printing.

- Brugge, David Chiliad. (1968). Navajos in the Catholic Church Records of New Mexico 1694–1875. Window Rock, Arizona: Research Section, The Navajo Tribe.

- Clarke, Dwight Fifty. (1961). Stephen Watts Kearny: Soldier of the West. Norman, Oklahoma: Academy of Oklahoma Press.

- Downs, James F. (1972). The Navajo. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

- Left Handed (1967) [1938]. Son of Old Man Hat. recorded by Walter Dyk. Lincoln, Nebraska: Bison Books & Academy of Nebraska Press. LCCN 67004921.

- Forbes, Jack D. (1960). Apache, Navajo and Spaniard. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. LCCN 60013480.

- Hammond, George P. and Rey, Agapito (editors) (1940). Narratives of the Coronado Expedition 1540–1542. Albuquerque: Academy of New Mexico Press.

- Iverson, Peter (2002). Diné: A History of the Navahos. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-2714-1.

- Kelly, Lawrence (1970). Navajo Roundup Pruett Pub. Co., Colorado.

- Linford, Laurence D. (2000). Navajo Places: History, Legend, Landscape. Table salt Lake Metropolis: University of Utah Printing. ISBN 978-0-87480-624-3

- McNitt, Frank (1972). Navajo Wars. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- Plog, Stephen Ancient Peoples of the American Southwest. Thames and London, LTD, London, England, 1997. ISBN 0-500-27939-X.

- Roessel, Ruth (editor) (1973). Navajo Stories of the Long Walk Period. Tsaile, Arizona: Navajo Customs College Press.

- Roessel, Ruth, ed. (1974). Navajo Livestock Reduction: A National Disgrace. Tsaile, Arizona: Navajo Community College Press. ISBN0-912586-18-4.

- Voyles, Traci Brynne (2015). Wastelanding: Legacies of Uranium Mining in Navajo Country. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Printing.

- Warren (January 27, 1875). "The Navajoes.—The Political party Returning from Washington and Who They Are.—Most Gov. Arny and His Views of the Indian Question.—What Kind of People the Navajoes area and What Their Country". Daily Journal of Commerce (Kansas City, Missouri). p. 1 – via newspapers.com.

- Witherspoon, Gary (1977). Language and Art in the Navajo Universe. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Witte, Daniel. Removing Classrooms from the Battlefield: Freedom, Paternalism, and the Redemptive Promise of Educational Choice, 2008 BYU Police Review 377 The Navajo and Richard Henry Pratt

- Zaballos, Nausica (2009). Le système de santé navajo. Paris: L'Harmattan.

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Navajo. |

- Navajo Nation, official site

- Navajo Tourism Department

- Navajo people: history, civilisation, linguistic communication, art

- Middle Ground Projection of Northern Colorado University with images of U.Due south. documents of treaties and reports 1846–1931

- Navajo Silversmiths, by Washington Matthews, 1883 from Project Gutenberg

- Navajo Institute for Social Justice

- Navajo Arts Information on authentic Navajo Art, Rugs, Jewelry, and Crafts

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Coordinates: 36°eleven′13″North 109°34′25″Westward / 36.1869°N 109.5736°W / 36.1869; -109.5736

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Navajo

0 Response to "Navajo Language Utah Is Known for Jewelry Design and Peforming Arts"

Post a Comment